The continental divide runs along the peaks of the Rocky Mountains and delineates the point at which streams flow either west to the pacific or east to the Hudson Bay and the Arctic Ocean. On my map I could see a faint dotted line marking the division. I began to think to myself that if I was about to cross anything as impressive sounding as 'The Continental Divide' then I must have not only climbed far higher than I realized, but I must also have a terrific descent waiting for me on the other side.

My map had marked on it a place called Swift River which was just barely back in the Yukon Territory. I arrived there soon, hoping to supplement my breakfast with some coffee and to use a restroom. Swift River turned out to be just two buildings joined together by a string of junk: old boards, bikes, tarps, several cars, and even an old school bus. Out in front were several ancient looking fuel pumps. Inside sat two men who looked as soft and rotten as the junk that sat out in the rain. The building was an old wooden house of poor construction. It was dark inside and the building seemed to sag under piles of old clothes and souvenirs collecting slowly in the corners. The floor echoed under my cleated shoes. By the kitchen in the back a sign had been hung that read, ‘Don't bother the help, they’re harder to find than customers.' A joke, sure, but a true statement, no doubt. I asked for coffee and the fatter man, who seemed more a part of his ancient chair than his own person, gestured with his finger to the man with bad teeth, who, with a severe limp, made his way back into the kitchen to fetch my coffee.

I answered the questions, where I was from and where I was going and yeah I had come across some bears and no I wasn't going to bike home when I got to Argentina. I paid the man for twenty cents of gasoline and went outside to fill my camping stove. I took several photos of the pumps and the junk, and set off again.

Up and over the continental divide and down the far side. On the map I could see the road run right down out of the mountains and into flat terrain before Watson Lake. Hours later, I reached the flatlands.

Well that's not true. I reached that point on my map where the subtle bumps of shading that represented mountains ends. In reality the terrain was steep and repetitive. Empty forests draped over hills large enough to make me very frustrated by the time I reached their peaks.

The junction for the Cassiar Highway drops south out of the Alaska Highway a solid twenty miles before Watson Lake. I decided that I carried with me enough food to just dive right into the wild Cassiar and avoid altogether the forty miles back and forth from Watson Lake.

Restaurants, convenience stores, and gas stations can, with a good level of reliability, be expected at any point where two red lines on the map meet, that is to say at a junction of two major roads (major being a relative term). Reaching the Cassiar, I saw with relief that the rule held true.

It was a nice building, made of large varnished wooden logs, and was arranged in such a way as to be accommodating. There was RV parking in the back and there were showers and a restaurant. Expensive as it was to camp there, I stepped into the gift shop to pay. The proximity to a good breakfast would make camping there entirely worth it.

As I approached the counter, the only other customer in the store, a man of about forty-five with a baseball cap and an ill kept moustache cut sideways in front of me. He had several white t-shirts draped over his arm, all bearing, in quivering blue letters dressed in ice, the phrase, 'I Survived the Alaska Highway.' The man paid for his shirts, and returned to his motor home.

The restaurant was good! The first place I had been that really seemed to be aware of the fact that food ought to have flavor, and put any effort at all into making it so.

'It's good!' I told the server who was also the owner. 'It's the first good food I've had in a long time! A lot of the places, well...I don't know, I feel like a lot of the places I've been don't really, they just don't-'

'I know,' the woman said seriously, and judging from her expression, not only did she know, but she considered the very idea of those other places frightening.

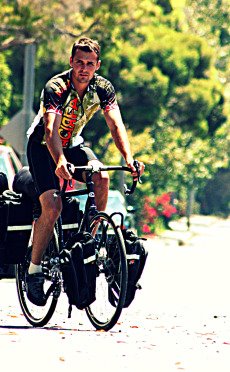

Cycle touring requires a comfort, or an acceptance of the unknown. I was at the head of a vastly remote and wild stretch of highway in northern Canada and knew very little more than that. Some people are able to frantically and fastidiously plan and research every detail, but I find that this limits one’s ability to respond and adapt to new situations. And on a trip of the scale I am doing it is simply impractical. I had only a rough idea of how long the road was and how long it would take me to get through it. I didn't know how much was paved or how cold it would get or how often there were other people or anything like that. I was uncertain about things as essential as food and water. The best information I could get on such topics was by asking locals, but the most they can tell you is, 'yeah, there are some stops. I think there's a grocery in Dease Lake.' Hardly conducive to a relaxed frame of mind, or to a detailed plan. As for water, my electronic water purifier had always been fussy and had finally died my last day in Alaska. I didn't know if there were at all frequent towns where I'd be able to refill, or even creeks whose water I'd have to boil. And then I would need fuel for my stove to boil the water and I had no idea how often there'd be gas.

Nevertheless, the following morning, after a good breakfast and real coffee, I turned right off of the Alaska Highway and simply began doing the work, began making progress, understanding that it didn't matter whether or not I knew all the details, but that with endless patience and effort I would emerge on the far side.

No comments:

Post a Comment