I carefully lifted the pot of icy water over my head, cringing where small drips splashed over the edge and fell on my bare torso. My feet and ankles were in that prickling burning frozen phase that comes before numbness and after the initial shock of the cold. I stood in the mouth of a large steel pipe that channeled the creek under the road. The creek was fed by water oozing out of the tundra in the summer heat like water from a sponge and moved just barely enough to keep from getting sick.

I took a gulping breath and upended the pot of water over by head, gasping as liquid icicles spread slender fingers down my body. I filled the pot again and poured it over my face. The water tasted salty from the sweat in my hair and on my forehead. I stepped a little deeper into the pipe to avoid the wind as I began to lather soap across my chest and down my arms.

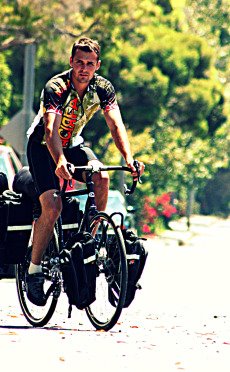

Three days. I had finished three days on the road and still I was stoic. I expected that I would thaw as my routine formed and that feelings and emotions would begin to flow and trickle over me in sometimes icy sometimes warm rivulets. But there was nothing.

I leaned over, and with a light and unhealthy scraping noise, picked up the light aluminum pot from the rock I had set it on and filled it again. I lifted it and poured it slowly down my hair. I imagined my first day washing off, imbuing the water with stress and pain and hard defiance. I dipped the pot again, its metal rim clinking against stones in the small stream, and poured it over my shoulders. Day two washed off in a dirty sheet of dust and sweat. It washed off in a sheet of rolling hills and low coiling bushes and black mudded river valleys.

I had awoken late the morning of my second day. Ten o'clock and my sleep still sat on me heavily, making me not want to move. Some combination of small pillow and hard mattress had caused my jaw to slide out of place. I moved it around slowly and with a strong internal, thock, it slid back in place. I felt a canker sore forming in the corner of my mouth and it seemed that one of my wisdom teeth had chosen that night to begin its painful debut. I rolled over and crawled out of my bag and staggered out of the tent. The day, once again, was the same as the day before. Plain white sky and empty cold wind.

The rain had stopped and I noticed with relief that it didn't seem to have saturated the road during the night. I noticed a small brown disc on the ground beneath my bike and picked it up. It was the plastic lid I had been using to place my kickstand on. It had cracked under the pressure in the night and that was why my bike had fallen over. I held up the lid and turned it over. It was still useable; I would just have to be very careful how I weighted it.

It took me a couple of hours to eat breakfast and clean up the campsite, so I didn't get started until nearly one. I pedaled slowly across the large parking lot back towards the road. The truck that had been parked at the other end of the lot, the truck that gave me company and felt like my friend, had moved on before I woke.

I made it back to the road and pedaled tentatively at first, unsure how violently my knee would object to being put to use again so shortly after the prior day’s abuse. Within a couple miles the pain returned, and the pain was worrying and wearying.

Trucks continued to pass, flinging me with rocks that sometimes stung and dust that coated my clothes and skin. Occasionally two trucks headed in opposite directions would pass me at the same time so that I was forced into the deep and dangerous gravel further on the side of the road.

The road was wide and elevated about ten feet above the tundra. Tall metal posts with reflectors at their tops lined the road so that its path would be discernible in the winter when even breath froze. Motorcyclists on rugged roaring beasts flew past in both directions several times an hour and usually gave some sign of recognition. My favorite of these signs was the clenched fist, raised and meant to impart strength. It worked.

The Alaskan oil pipeline, the only reason that there's anything this far north anyways, materialized out of the haze to the right of the road and ran parallel to it. Large signs marking the mile of the pipeline came with it and reminded me how slowly the miles were passing.

52, the last one I've noticed said 52. I thought, the next ones got to be like 57... Or maybe even 58. In the distance the orange sign came closer and closer until, finally, it was legible. A large 53 was inscribed across it in big black letters. That was the way it went. Miles crawled by. A minute never passed that I wasn't painfully aware of. Time was eternal. Feet added to feet and very, very slowly added to miles.

Out of the haze in the distance I saw some large structure loom, like some gaudy fictional city of spires and light and steel. What on earth? I wondered as I drew closer and the towers became more solid. I thought there wasn't anything for hundreds of miles. Because the haze made everything look more distant than it was I quickly arrived at the structure. A chain link fence surrounded it and there was a sign on a metal post across the street that said 'Pump Station One - No Services.' I rode by staring up at the structure, wondering what other bizarre things were lurking in the haze ahead.

At last the road made its first turn, a big yawning turn to the right, stretching and flexing its muscle like the first stretch you make in the morning after a night of good sleep, arms wide and fingers curled. After this, the road seemed to wake up and dove headlong into the first hills rising out of the tundra. I climbed it slowly, inevitably, taking care not to strain my knee.

Far beneath me to my left, the river veered away and I bid it farewell and regretted never getting to meet it. I climbed and found that I could climb. The temperature had come up and it was warm now, in the seventies, and I was sweating. The road fell and then rose again, steep and rocky. And then again it fell and climbed. And again and again it rose and fell, climbing as aggressively as possible over the rolling hills, turning only just enough so that a truck could rumble up the hill in its lowest gear. I sure hope there's a point to all this up and down, I thought. I kept climbing. After some time I would peak the largest hill on the horizon expecting to look from its peak and have a clear and distant view of where I was headed and where the road flattened out but was always disappointed in seeing more hills identical to the ones I had just climbed. Minutes still ticked by with painful lethargy and I tried not to look at the mile markers because I already had learned that they told discouraging lies.

The road curved around and began a long descent. I had not realized that I had climbed so high. It was steep and I was moving quickly, a bit faster than I felt comfortable with. The road was bumpy and curved sharply. A semi blasted from behind me and I slowed slightly as it flew around a blind corner leaving me in a cloud of dust. The road dropped further and as I came around the next corner I realized that it was dumping me back along the river. Great. Thanks for that. You know we could have just stayed down here. I hope you got that out of your system, I muttered to the road.

The road, it turned out, had not gotten it out of its system and continued to shoot randomly up into the steep hills to the right of the river, roller coaster along for a while, and then plunge back down into the valley. It was wearying and I pushed along hard, not leisurely cruising, but sweating and breathing hard and working hard. The miles inevitably began to stack and I reached forty, feeling pleased that I had been able to match the previous day. In the haze ahead, partway up the next hill, something quivered into form.

'I can't let you ride here.'

The man was maybe forty. His skin was red and peeling lightly from, as he later explained to me, getting a cold burn several years ago working the road in the winter. He still had most of his teeth but it didn't look like he put too much effort into trying to keep them. He wore jeans, work boots, a hardhat and an orange reflective vest.

'You'll have to ride in the back of the truck, it's only a couple miles. We're working here and it's not safe.' he said. It was only my second day and the idea of getting a free ride for a couple miles both tempted and appalled me.

'Is there no way I can ride it?' I asked him.

He eyed me and my bike for a minute and then said, 'I can understand you wantin’ to ride the whole thing. We had some biker come through here last year, rode all the way from Argentina and then we made him go in the truck. It was the only part he didn't ride. I said to him don't worry, I won't ever tell nobody.'

I stared back thinking well you're telling me now, I wonder how many other times you've told this story. After a pause the man said, 'I tell you what, I get off in an hour, or an hour and a half, or half an hour or somthin’, whenever the trucks stop coming. You can ride through then. You can just wait over there,' he pointed to the side of the road behind his parked truck. I pulled over and sat on the ground and pulled out my bags of food. The worker spat some words into his walkie talkie and some other words spat back out of it. Then he turned and stared at me shamelessly, taking in every detail of my appearance and making me feel uncomfortable.

'I'm Ken' he said.

'Dave,' I answered.

'Where you goin?' he asked.

'Fairbanks and then Argentina,' I said.

'You goin’ alone?' he asked, still staring at me too concentratedly.

'Yeah, that's the plan,' I said.

He looked at me a moment and then said,

'You guys are all crazy. Do you have enough food?'

I told him about the food I had gotten in Deadhorse and how I thought that it was enough.

'I got some in my truck, if you want it,' he said, half starting towards the car.

'Sure!' I said, 'If you don't mind.'

He fished around in the car for a minute and then handed me a snack size bag of Cheezits, trail mix and a mostly empty bag of jolly ranchers.

'It's not much,' he said apologetically.

'It will help,' I said, 'thanks very much.'

He smiled at me, feeling immensely proud at the tremendous good deed he had just done.

'Sure' he said, 'I think people ought to help each other. You know, just when you can, kind of do a good thing for somebody.'

'Course,' I said, 'you want some beef jerky?' (beef jerky was one thing I had plenty of)

'Oh no, no you need it.' he answered smiling. He knew he had just been elevated to sainthood and he wouldn't let any charity on my part detract from his nearly divine status.

'I've got some water too.' he said, the idea just coming to him as he dove back into his cab and emerged with two bottles of water.

'Oh I don't want to take all your food.' I protested feebly, knowing that there was no stopping this force of goodness now anyways.

'Oh that's alright. It's all free at the camps anyways.'

A white pickup headed the other way pulled up next to us and stopped.

A man with a sparse but long white beard leaned out the window and said in a quiet, serious voice, 'Well that's the last truck, Ken.'

'This is Dave' Ken said proudly, gesturing towards me, 'I've helped him out, given him some food. He's going to Argentina.'

'The man in the truck stared at me seriously, behind serious sunglasses and then said, 'You got bear spray?'

'Uh yeah. Yeah I do.' I said.

'Good,' he said quietly, looking over me and my bike. 'Remember, if a bear attacks you, you just play dead, but if he starts to eat you, you kick him in the balls.'

I looked back at him, trying to detect some trace of humor in his expression. There was none.

'Uh, yeah. Good to know,' I said.

He turned in his seat and pointed back up the hill the way he had come. 'Stay on the left side of this hill,' he said, 'the left side has been compacted, the right side is still soft. The left side.'

White beard put his truck in gear and drove away slowly. Ken turned to me to make a big goodbye out of our parting.

'Just, uh, take care. Be careful,' he said, looking like there was something more he wanted to say.

'I will,' I said, positioning myself on my bike and getting ready to leave.

'Vaya con Dios,' Ken blurted awkwardly and then looked nervous about whether or not he had said the correct thing.

'Is that right? I mean, that means... Uh that means...'

'Go with God,' I said, 'yeah, you said it okay. From Pointbreak right?' I asked him as he had pronounced the words in exactly the same way as Keanu Reaves does in the movie.

Ken looked affronted, 'Yeah - no- I mean... It's a little more deep than that.'

'Of course, I'm only kidding. Thanks very much. I really appreciate your help,' I said, trying to mollify him. I clipped in and began to make my way slowly up the left side of the hill.

A few miles further on the pain in my knee had spread out around the tendons and muscles surrounding it and it moved from pain to weakness.

It felt as though the joint were made of a material not suitable for the stress and that at any point it simply would stop to function completely. Climbing the final hill that day was the first time the pain reached a cry-out-loud level. Three times spasms ran up and down my entire leg, a sharp and shocking pain over the top of what I was used to dealing with. I saw a small pull out up ahead and coasted over to it, relieved to have a place to stop.

The turnaround was small and with my tent set up at the back end of it, I was still only about eight feet off the road. A few feet behind my tent was a small pool of stagnant water from which poured thousands of giant mosquitoes.

I quickly dug into a pocket on my handle bar bag and found a bottle of 100% DEET. I squeezed some drops into my palm and then smeared it into the mess of dirt and sunscreen and sweat already covering my face, neck, legs and arms.

If mosquitoes are supposed to be repelled by mosquito repellent, then these particular ones missed the memo. The large things hummed around me with an audible buzzing noise as I slapped at them constantly. As quickly as I could, I changed into long sleeve clothing and then dug to the bottom of my bag and retrieved a hat with mosquito netting built in which covered my face and neck. The only part of my body that was exposed was my hands, which I kept moving constantly to prevent the mosquitoes from biting them. I set up my tent, trucks still roaring past, and threw my stuff inside as quickly as possible to prevent mosquitoes from flying in through the door. I had a quick dinner and then packed my food back into its bags and looked around for a place to hang them.

The pipeline was perhaps a hundred yards away and I thought about going over to it, but the grassy tundra had gotten deeper, mile by mile that day, and now was covered in hard, waist deep bushes. There was a sign post across the road set about 20 feet into the bushes marking an underground pipe. Why on earth there was an underground pipe there I still cannot guess. After much struggling with my nylon cord and heavy awkward bags of food and unyielding bushes, I had managed to hoist the stuff as far as I could up the sign. I stood back to admire my work. The bags hung pathetically about five feet off the ground and the sign now leaned at an awkward angle, threatening to uproot under the weight. As I watched, the cord slipped and the bags fell a couple of inches lower. Well that's the best I can do tonight, I thought, somewhat annoyed.

The pool of water next to my tent was too disgusting and too thoroughly guarded by mud and bushes to draw water from, so I conserved what little I had, brushing my teeth carefully and measuring what I drank before crawling into my tent and quickly sealing the door behind me.

On the ceiling, a half a dozen mosquitoes buzzed around, banging against the mesh windows. I reached out quickly and caught one in my hand, crushing it. These things are about the size of hummingbirds, I thought, hummingbirds that suck your blood. I deposited the large insect into a paper napkin and reached up and caught another. Actually that's a good name for them. 'Hummingbloods.' Charming. and I deposited the second insect into the napkin. As I caught the rest I wondered what on earth they must eat when there are no people around.

Finally, dirty and sticky, I fell asleep.

The noise of a truck along the Dalton highway is unlike anything else. You can hear it roaring miles away, smooth and piercing and powerful, almost indistinguishable from a jet engine at a distance. Then, as it gets closer, the pure jet noise is supplemented with the rumbling of tires, the grinding innards and changing gears of the machine. It is loud. You would not believe how loud it is in the otherwise perfectly silent world. As I lay in my tent, half asleep and only a couple feet off the side of the road, it sounded like the noise was coming straight towards me and I had to tell myself again and again that I was not going to be run over as I woke up from dream after dream in which I was crushed under some giant machine.

Despite the noise I managed some decent sleep, and then, in a moment of silence, there was a voice.

'Hello? Hello?'

I turned in my sleep, sure that the voice was part of my bizarre dreams. Then the voice was much closer, the undeniable reality of it harshly contrasting with the expected ambiguities of my dreams.

'Hello!'

I rolled over quickly, looking out of the mesh of my tent towards the road. A stooped figure dressed in all black was creeping tentatively towards me. He had long black hair and a scraggly black beard. He walked as though he had lived his whole life in a cave whose ceiling was too low to allow him to stand all the way upright. As he walked his hands absently clawed the air ahead of him as though feeling for spider webs.

'Yeah?' I said, feeling around for my can of mace.

The man crept right up to my tent, so close I could see the dirt on his face.

He surveyed me for a moment and then said, 'You know where Happy Valley is?'

I relaxed. Happy Valley, I knew, was the work camp along the river about ten miles back.

'Oh, yeah,' I said rubbing the sleep from my eyes, 'it's about ten miles that way, on the right. You can't miss it.'

The man was quiet for a moment and then noticed my bike, 'You on a bicycle?' he asked.

'Oh, uh, yeah. I am,' I answered, wanting to go back to sleep. The man was quiet for a long moment, thinking deeply. Then he asked, 'Are you crazy?'

'Yup,' I answered immediately, rolling back over and pulling the sleeping bag over my head. I heard the man slowly creep away, get back in his car and drive off. I fell asleep again almost instantly.

Beneath the Atigun Pass

Hundreds of small slimy fingers rushed up at me and then in unison pulled away momentarily before reaching up again in a synchronized dance. I stood crouched on a low flat stone near the edge of the river, staring into the water and watching the strange mossy tendrils swirl in the current. This was the first time I had filled my water bottles from a non stagnant source and I watched with pleasure as the plentiful clear water poured into their open mouths with a slight gurgle. I hoped to make it to Galbraith that day, a full ten miles further than the day before, twenty miles further than the first day.

Day three had been a near exact repeat of the second day, except that the rolling hills had rolled higher, and to the side of the road the first small efforts of the Brooks Range to make mountains rise high above the road. The third day, like the second, had been full of sweat and short of breath and time. It was hotter today, into the eighties, and was humid. It rained a little as I rode, which felt good in the mucky air and the heat.

The road still seemed to prefer a good hill to the flat smooth river valley, to which it frequently returned in order to remind me that there was no purpose whatsoever in ever having climbed the hills to leave it. At times the road was smooth as glass, a moist, packed river mud that glazed by undulating with a wet noise under my tires. Other times it was gravel and deep and rocky and hell. There were small slow creeks every ten miles and pools of dead water everywhere. Time still passed with intolerable lethargy and my knee still hurt, but did not feel worse than the first or second day.

I capped my bottles, climbed back onto my bike and began moving slowly up the next pointless hill. I worked for miles more, swatting at mosquitoes and beads of sweat that felt like mosquitoes. Dust continued to build on my skin and clothes. Another truck blasted by, incredibly loudly. A large chunk of gravel shot from behind it and struck me hard on the cheek, stinging. An impossible amount of time later, and after an impossible number of hills, I arrived at Galbraith, where a small oozing creek ran under the road.

It was paradise, camping there. The mosquitoes were tolerable and fresh water was abundant. I was a good ways away from the main road on a secondary road that led to an old airstrip. After setting up my tent, I grabbed my cooking pot and my soap and towel and waded into the cold water by the mouth of the large steel pipe that channeled water under the road. I filled the pot and, after taking a large breath, poured the water over my head.