Every half hour there was a loud, long humming noise. It sounded like a distant prop plane or a vibrating sander. It would switch on suddenly, moan along for about a minute, and then switch off completely. Other than the noise of the light rain falling, whose volume was amplified against my tent, there was no other noise. It was completely black but my eyes were open. I leave my eyes open even when I'm trying to fall asleep. I turned in my sleeping bag like a chicken on a rotisserie, exposing my left shoulder and hip to the ground, to the fire that would within a few minutes cook that half of my body to a level of discomfort that would require me to rotate onto my stomach, and then my right side, and finally over onto my back again, leaving me evenly cooked all around and ready to begin another turn.

The humming noise sounded again. It was made by trucks crossing the long bridge that stretched over the pale milk chocolate river a quarter mile away. That much I knew. What I didn't know was that the surface of this bridge was made of a large steel grid. I didn't know that it would be so cold in the morning that it would still be raining and that the steel squares of the bridge would be slicker than ice under my tires.

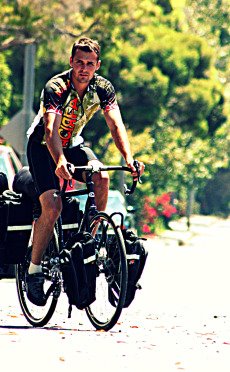

So the following morning I rode towards it at a confident speed, naive to my impending misfortune. When I hit the bridge, the heavy back end of my bike drifted out sideways like a dirt track motorcycle racer would do to drift around a turn. The front wheel shifted quickly one square to the left and then shot back in line. My stomach cinched up and I knew I was going down. I tried to unclip my right foot from the pedal to help catch my fall, but before I did the back tire suddenly shot back into alignment as though pushed by an opposing force. Shaken and moving more slowly, I tentatively pedaled on. A second later, the rear tire drifted suddenly out to the right and once again I really felt that I couldn't save it, but just before I completely lost control, the bike corrected again. I tried shifting my weight forward and back, I tried going faster or slower, but I couldn't understand the physics of the thing. The bike just kept drifting wildly and unnervingly to the side before suddenly correcting again. The whole trip I don't think I have had such an arm and ab workout as I did then trying to stay balanced while drifting across the bridge. I was almost across, the last fifty feet, when the rear tire started drifting sideways again. Hold onto it, I told myself. It will correct in a minute, the back end of the bike hung in balance for a moment as the rear tire spun slowly at a diagonal. Just as I thought I had it, the back tire shot out suddenly, the bike careened around sideways, and I fell flat down on my side before I even realized what happened. I stuck out my hand to catch my fall and it slapped hard against the ice cold steel bridge as my bike landed on top of me, my feet still clipped to the pedals.

I’m alright, I realized as I picked myself up. Well except for my hand, but I don't think it's broken... I hoisted the bike upright and walked the remaining distance to solid ground. I looked back at the bridge which now seemed a forbidding dark tangle of wet steel in the cold grey morning light. It was my first fall, my only fall so far, and while I did have the cold shivers of adrenaline shaking through my hand, I felt lucky. If there had been a truck behind me...

The road I was on is called the Alaska Highway. It is perhaps incorrectly named given that the majority of the road runs through Canada, but the Alaska Highway it remains. There is a point where the Alaska Highway dips briefly into British Columbia before crawling back into the Yukon Territory. You can easily see this by looking on a map of the area, and my goal for the day was to get through the portion in British Colombia and back into the Yukon. I didn't make it.

It turned out to be much farther than it looked on the map and I ran out of energy that day. Tired, and having already ridden farther than I planned, I pulled over to camp in the grass along side of the road.

The grass was deep and heavy with water from the incessant drizzle. Small black spiders and ants hid from the rain on the underside of the blades. I pushed my bike away from the road and flipped out the kickstand with a twang. The bike would not stand up; the kickstand just sank straight into the muddy ground beneath the grass. Finally I managed to keep it upright, jamming the kickstand against a small rock, black and slick with mud. I began feeling around for a flat spot, using my feet to feel the undulations of earth concealed by the grass. Nowhere was really flat, but I finally found a place that was close enough and where the water wouldn't pool.

Seen from a passing car or truck, or out of the window of a warm house, a tent seems impossibly small, pathetically uncomfortable, sad and alone in the rain. But on the inside, with much fussing and organizing and drying off and cleaning up, it is possible to be fairly comfortable in most situations. This was one of my worst campsites, in the deep, wet, awkward band of grass dividing the highway from the forest, close enough that a passing semi was loud enough to wake you, without water or a shower or a place to get food. But even still, I managed to change into dry clothes, tuck my wet, clammy feet into good wool socks (the socks from Jesse’s friend), eat a decent meal, read my book, and even listen to music while doing it.

The following morning it was still raining. Even a light drizzle sounds loud as it pops against the top of the tent, making it easy to think the rain is much heavier than it actually is. I always took some pleasure in making breakfast, leaning out of my sleeping bag and warming water for oatmeal and tea. But it was raining and I didn't want to cook out in the rain. I decided to try and use my stove inside the vestibule of my tent.

My camping stove runs on gasoline, an ill suited fuel for the purpose, but one that was very practical for me since I could refill it nearly anywhere. I took out my stove and fuel canister from their little black canvas bags and flipped out the little aluminum feet of the stove. Using the pump built into the top of the fuel can, I counted to twenty as I pressurized the bottle. I inserted the braided steel fuel line into the nozzle on the canister, locked it in place and opened the pressure to the fuel line. Now for the tricky part. The stove will not burn properly until it warms up. To do this you are supposed to bleed a tablespoon of gasoline onto the wick and let it burn a big smoky fireball for several minutes. This can sometimes be dramatic and a little unnerving. More than once I had found myself scrambling to move pieces of paper, plastic and articles of clothing away from a larger than expected fireball after accidentally letting out too much gas.

I mashed down a section of grass beneath my rainfly and balanced my stove on its aluminum base. I pulled my lighter from inside my shirt where I had been warming it in order to be ready to ignite the fuel. I flicked open the collapsible flame adjuster and gently twisted it open. A small amount of gasoline sputtered and bubbled in the center of the jet. I quickly shut off the fuel supply, snapped open my lighter, and held it to the little puddle of fuel.

It didn't take for several seconds, but then I whipped my hand away as it suddenly exploded into a bright orange fireball with thick black smoke. Instantly the inside of the tent was warm. The heat seemed to soften the wet fabric of the tent, which started to sag down closer to the flame. I reached around the flame to press the canvas away from the fire and with my other hand unzipped the door of the rainfly partway to let some of the smoke and heat out. Small droplets of cold rain snuck through the crack and landed on my pillow, disappearing instantly into its black fabric. After a moment the flame died down until it was barely visible, like the flame of a candle. Gently I eased open the fuel line just enough to let a small amount of gas through.

The stove had not yet warmed up properly so the gas that now seeped through the nozzle was part vapor and part liquid. This caused the stove to spew a rapid series of fire balls with a loud puff puff puff puff! A moment later the explosions diminished and the flame began to burn a hot blue.

I pulled apart my cooking pots, filled one with water, and placed it on the stove. The flame sputtered again as I cranked it up to full power and felt around the stove with my hand to see how much heat it was emitting at its edges. It seemed ok, barely.

I closed the flap a little bit to stop the rain from coming in, scooted around, and grabbed my bags of food. The bags were long cylinders, simple and light. As this was the case, I often had to pull everything out of them in order to get what I actually wanted. A minute later, my sleeping bag was lined with food: the beef jerky from Deadhorse, vitamins, rice meal, several powdered supplements, a handful of snickers bars, a bag of sugar, salt and pepper, dried apricots, canned cashews, trail mix, peanut butter and jelly, two oranges and an apple, crackers, pasta, chili, powdered milk, honey, tea, and finally, my oatmeal.

I poured several bags of the oatmeal into my silicone bowl and added in powdered vitamins, honey, and a spoonful of powdered milk.

The little stove sounds like a miniature rocket when it gets warmed up, so much so that I actually checked to see if it generated any thrust the first couple times I used it.

I took the cap off of the pot and a cloud of steam mushroomed out of it. I added the boiling water to my oatmeal concoction and threw some tea into what remained in the pot.

The rain continued lightly and loudly. I unzipped the door a little further, struck by a sudden fear that I had forgotten to zip up the bag on my handle bars. I peeked through the crack and saw the bike a few feet away, sad and wet, but perfectly in order.

Breakfast was too nice. It made too perfect an excuse to linger in the tent and avoid the work, avoid the cold, and avoid the rain. But ultimately, somehow, I put myself in motion gathering up all my food and cooking gear, dumping the small amount of water remaining in the pot into the grass, and organizing all the rest of my stuff into piles.

Crawling to the side, I rolled up my sleeping pad and stuffed the sleeping bag into its case. Now the dreaded part: I pulled off my warm pajamas and slid into my still wet cycling clothes. My socks were still drenched as were my shoes which bubbled water as I squeezed into them. I pulled on my rain jacket and my wide brimmed hat and hoisted myself awkwardly out of the tent.

Rain is not ideal, but it is actually not so miserable to bike in, provided it’s not too cold and that you accept that you're just going to get wet. The worst part of rain is actually the setting up and tearing down of a campsite because all of your stuff gets wet in the process. I had laid awake the night before thinking of a way to avoid this. I quickly and carefully removed all the gear from inside the tent, tucking it inside 'waterproof' inserts inside my panniers and then covering the panniers with external 'waterproof' covers. This was the only way that I was able to keep my gear mostly dry. I then turned my attention to how to get the tent and rainfly packed up without getting the entire tent wet. I first went around and pulled out all the tent stakes that were holding the fly and gathered them up in one muddy little pile.

The cover now adhered in its wetness to the tent underneath. Reaching under the rainfly I unclipped the tent poles and popped them out from the four corners of the tent. There was now a deflated pile of wet nylon at my feet with tent poles sticking out at either end. I disassembled the poles so that they would slide out smoothly and pulled them out from the other end. After folding them up and stuffing them away, I yanked the tent out from beneath the cover and crumpled it into my pannier and followed it with the sopping wet rainfly.

Ready to go. At least so I thought. To do it properly I still had to brush my teeth and put on sunscreen and dig my gloves back out and clean my glasses and then I could go. I thought about it for a minute and then decided not to do any of those things, but pushed my bike carefully through the grass, up the little embankment, and back onto the road.